Partner Partner Content Deliberating the D Word (Density)

Density, increasing the number of people living in a specific geographic area, is both desired and dreaded. Desired, for the benefits, dreaded for the (mis)perceptions.

In 1950, the city of Cincinnati was home to 502,000 residents. The city; not the county, not the region, but the city itself. According to the 2020 census, the city has 309,000 residents. Could Cincinnati, with its challenging geography and existing housing shortage again accommodate 200,000 more residents?

“If you’re not growing, you’re losing relevance, or worse, shrinking,” said Douglas Marsh, Associate AIA, with KZF Design. “We know that the region is going to grow, so we want make sure it’s growing in a manageable, controlled manner.”

“Cincinnati is a prime candidate for growth because the infrastructure and historical housing is here,” said Michael McInturf, AIA, Professor of Architecture at University of Cincinnati and with michael mcinturf ARCHITECTS. “The framework was laid out years ago and we have a lot of room within it to grow.”

Density, increasing the number of people living in a specific geographic area, is both desired and dreaded. Desired, for the benefits, dreaded for the (mis)perceptions.

Why Density?

The elements necessary for a thriving municipal economy include residents, places to work, services, and activities.

“The more people you have in a neighborhood the more chance meetings you have, the more opportunities you have to be social, and sustain that coffee shop around the corner,” said Jeff Raser, AIA, with CUDA Studio. “Neighborhood businesses need density, and density is the ticket for people getting the neighborhood services and amenities they want.”

“In downtown Cincinnati the need for density is part of the reason you’re seeing more apartment and condo development occurring,” said Marsh. “The other components required to form a community need density: retail, restaurants, and bars et cetera. Density is sometimes considered a bad word, but for businesses to survive, there needs to be a certain density of workplace and residential.”

Increasing population density also impacts sustainability and health.

“Dense cities have less carbon emissions,” said Hyesun Jeong, Associate AIA, with the University of Cincinnati’s DAAP School of Planning. “If we consider the environment not just for our generation but the next, how we build cities impacts how we live in the next hundred years.”

Shared walls of multi-unit buildings help lower heating and cooling needs. Lower-carbon transportation options, including public transit, walking, and cycling, see higher usage in denser communities.

“The great thing about living in a walkable neighborhood, whether you’re going around the corner to the coffee shop, or just walking the dog, it’s mentally helpful to see other people or meet a neighbor getting out of their car,” said Raser. “The sidewalk is the most wonderful meeting room in America.”

Growing the population through density also has economic benefits for municipalities and for other residents.

“Civic infrastructure, including police and fire departments, depends on having a healthy tax base,” says Raser. “Density is fiscally responsible from an infrastructure, taxpayer, and fiscal perspective. If you have a ten-mile-long road with ten residences on it, you can only spread the cost of road, utility, and municipal services among ten homeowners. But if you have 30 residences on that road, it decreases everyone’s costs.”

Concentrating residential areas around business districts doesn’t eliminate the need for cars but can reduce the space required for cars. Streets can be narrower, reducing traffic speed and car-related injuries. Parking lots can be shared by the dentist office during the day and the restaurant in the evening, freeing up land for greenspace or additional development.

“The conditions of a vibrant, living environment need people,” said McInturf. “If people are here, then businesses want to be here, the people who work in those businesses need childcare which creates another business. It feeds true economic development.”

Density also allows for a variety of housing types – single family, row houses, multi-family – and sizes. Which provides more opportunities for people at all stages of life – college grads, singles, young families, empty nesters, and seniors – to stay in the neighborhoods they love. But in Cincinnati, 77% of residential zoning is limited to single family homes.

“If you raised a family in a community, but now don’t need such a big space, are there other options to stay there?” asked Marsh. “Zoning limits what housing is permitted. We need to look at those restrictions to make sure we’ve got a balance of the type of housing that’s available. Having all single-family housing doesn’t work, but having all apartments doesn’t either; we need to have a mix.”

Affordability is another benefit of density. Housing shortages increase prices of home sales and rent, an impossible situation for low-income households, but also for working- and middle-class households. Multi-family and smaller lot options can be more cost effective for developers and consumers. In 2017 Minneapolis changed the zoning code to allow for more units to be built on all residential lots. In five years, the city’s housing stock grew by 12% and rents only increased 1% (rents increased 14% in the rest of Minnesota over the same period).

Defining Density

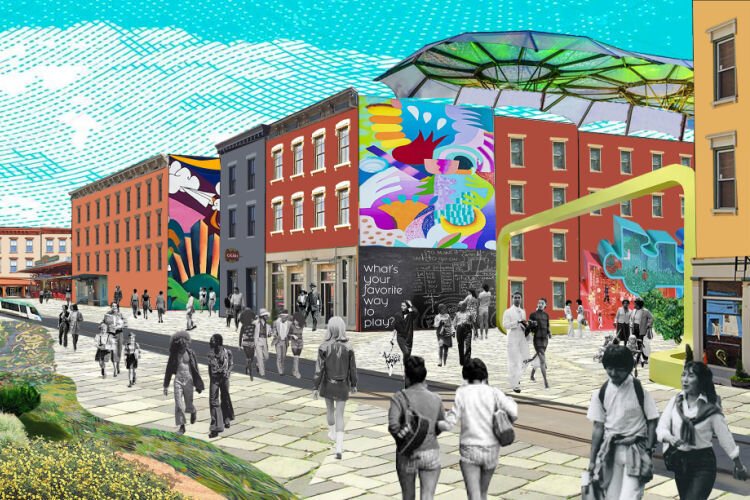

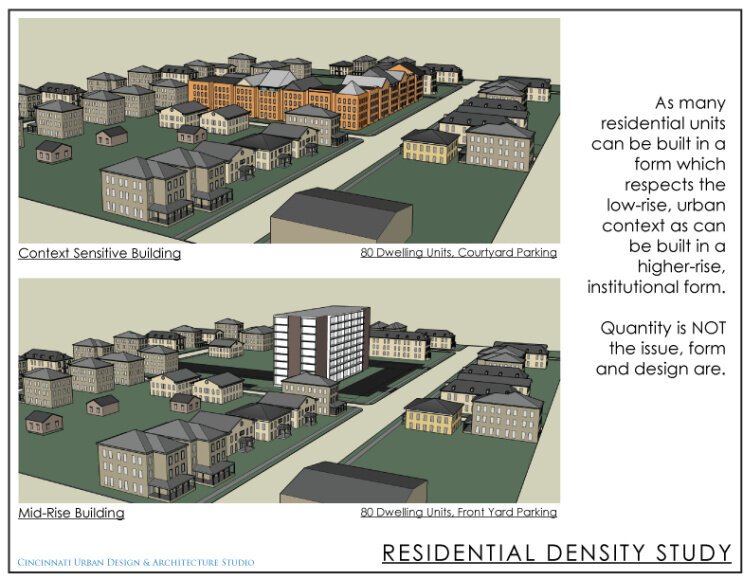

One of the demons haunting the density discussion is the image many people have of mid-twentieth century high-rise apartment buildings surrounded by parking lots or concrete plazas.

“We’ve seen a lot of failures of that version of density,” said Jeong. “More successful options exist. We can have high rise buildings that are not isolated; they’re surrounded by communal spaces, transportation, amenities, restaurants, and markets that connect people.”

“Design matters,” Jeong continues. “Density can be achieved in different ways. It doesn’t have to be all towers; it can be a townhouse, triplex, or duplex in variety of architectural styles, materials, and heights so it doesn’t look monotonous, with green space in between or a shared courtyard.”

Density is not limited to big cities or downtowns. Small towns and neighborhood business districts also need a concentration of people in order thrive, so the type of density must fit the community.

“A ten-story high rise apartment building surrounded by parking may be completely out of place,” said Raser. “Instead, you could get the same number of apartments in three-story buildings spread over the entire site. Density can be achieved in more architecturally appropriate and community friendly ways, a gentle density. Accessory Dwelling Units [ADUs] for example have been in neighborhoods for 100 years as an apartment unit over a carriage house or garage.”

Gentle density also involves allowing for smaller lot sizes and structures. With more flexible design options, developers and residents may see lower costs.

“Communities need enough density to bring in a diversity of businesses, eateries, and restaurants” said McInturf. “Can it be too dense? Yes of course. But that comes from not enough diversity in the type of living and working structures.”

A more flexible approach to zoning, including mixed use and a variety of housing typologies, allows communities to adapt density to fit their unique needs.

Concerns about Density

“In American cities there is hatred toward density,” said Jeong. “People tend to value privacy and individual space related to zoning regulation. Zoning, including parking requirements and separating different uses, makes density challenging or impossible in some places.”

When it comes to density, the fears are predictable: crime, traffic, and loss of community spaces.

Crime is all about people, but more people doesn’t mean more crime. In fact, it’s possible that more people leads to more eyes watching and awareness which could reduce crime. But the density=crime belief is pervasive.

More people doesn’t mean more cars. A concentration of people can support better public transit and walkable or bikeable communities. Reducing parking requirements also makes development more affordable as parking can be 10-18% of building development costs. Eliminating that expense helps developers building new projects and allows small business owners to invest more in their business.

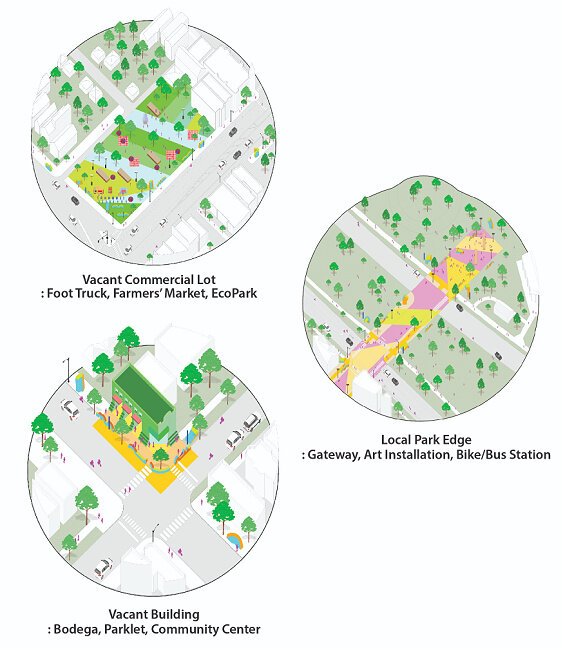

Increasing density also doesn’t require sacrificing greenspace.

“Cincinnati and the region are known for having a robust park system, as well as great sports, food, and arts,” said Marsh. “It’s one of those critical aspects of what makes a great city. Our density shouldn’t grow to the level where we’re eating up park space. Densifying around green space so that it becomes a ‘front yard’ makes those developments even stronger.”

Other cities have had success with re-greening urban areas and encouraging development around natural amenities. The Cheonggyecheon area in Seoul, South Korea removed an elevated highway to daylight a stream. Could Lick Run in South Fairmount see similar development? Klyde Warren Park in Dallas, Texas created greenspace on decks built over a highway, comparable to the proposed Fort Washington Way project.

“Capping Fort Washington Way with a park would make the empty lots on Third Street interesting and viable,” said McInturf. “It encourages development plus creates a public space for the city.”

Building new parks and density around public spaces creates a resource that can be used by an entire community.

“Green infrastructure can use vacant lots and underutilized spaces,” says Jeong. “We can reuse land that is already available. Grey urban infrastructure like vacant lots and underpasses can be turned into community pocket parks or hanging gardens.”

The impact of density on existing infrastructure is frequently raised. Cities across the country are struggling with aging bridges, sewer systems, and other critical municipal services. Rather than being a negative, creating density can provide an opportunity to replace outdated systems and generate additional taxes for municipalities to improve services for everyone. Increased use of alternative transit can lower road usage. Adaptive reuse of existing buildings may reduce demand on public services.

“People jump to conclusions about density’s impact on infrastructure,” said Marsh. “It’s not that we don’t need infrastructure improvement, but the loads are significantly different. If you think about an office building downtown that might have 1,000 people working in it, its utilities are sized to accommodate those 1,000 people, but if you convert that building to condos, you’ll have 100 or 200 people living in the building.”

Density, Cincinnati Style

Cultivating more densely populated communities can, and should, be done in ways that fit the needs and resources of specific communities. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to creating density.

Acceptable levels of density change over time. At its peak, Over-the-Rhine was home to 45,000 people. While that level of density isn’t appealing today, the neighborhood can accommodate more than the 5,600 people living there now.

“Density comes in orbits with the highest around the business district, then tapering down,” said Raser. “In Clifton the neighborhood business district on Ludlow has apartments on top of the shops and around them are apartment buildings three or four stories tall. A block away you’ll find duplexes and rowhouses. Move another block away and there are small houses on small lots. It’s a wonderfully walkable neighborhood with a diverse mix of housing types and street vitality in all the right places. And enough density to support a grocery store.”

The Cincinnati region is fortunate to have a variety of neighborhoods and communities. Increasing density is possible, and necessary, everywhere, but the specific solution – smaller lots, mixed use, ADUs, high rises – must fit its surroundings.

In Cincinnati, focused planning can be seen at The Banks, Washington Park, and Fountain Square. Identifying opportunities with the same, or greater potential, to add residents and businesses is essential for a growing and vibrant city and region.

“You see nineteenth century infrastructure being rejuvenated all over the world,” said McInturf. “Queensgate is an opportunity to do something unique. What if Smale park stretched to the west side? Could 80 Acres develop urban farms? The Mill Creek watershed and abandoned rail yards all have potential for public space with density around it, not just homes but businesses.”

To build for the future, Cincinnati and the region need to consider what density looks like at all levels: micro (individual or groups of blocks), neighborhoods (surrounding business districts), towns and cities, and the region as a whole.

“If we’re going to grow the population, you have to think about what that means as every decision made along the way could create problems,” said Marsh. “Let’s spend the time and energy now to dream and develop a plan; a plan that doesn’t go on a shelf but is used as a guide and monitored.”

Tristate residents can engage in discussion about the future growth of the region happening around the City of Cincinnati’s Connected Communities, the Brent Spence Bridge, Fort Washington Way, the Western Hills Viaduct, and the Cincinnati USA Regional Chamber’s Embracing Growth and Cincinnati Futures Commission.

The Architecture Matters series will also continue the conversation with future articles and panel discussions. Learn more here about the speakers and moderator for the Deliberating the D Word (Density) panel discussion coming up on June 6, 2024.

The series, Architecture Matters, is supported by AIA Cincinnati. Learn more at aiacincinnati.org.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the American Institute of Architects or the members of AIA Cincinnati.