One tree at a time: Teens work to reverse decades of environmental injustice

Groundwork Ohio River Valley's grassroots approach starts with asking residents what they need for healthier, sustainable neighborhoods.

Across the region, there’s a big disparity in how long people live. Nearly 90 years, on average, in Indian Hill and Mason, but barely over 60 in Arlington Heights and Adams County. That’s nearly 30 years of life, love, children, grandchildren, and memories that are lost. Why? Community health experts are looking at the larger forces that shape health and wellness. The places where we grow up, live, work, and age shape our lives and our opportunities to thrive. This is the sixth story in the series, Health Justice in Action, a year-long deep dive into the factors that people and neighborhoods need for long, healthful lives.You can read other stories in the series here.

In an alley next to Saint Michael’s church, a dozen young adults select bicycles from a garage, check the tires, don helmets, and prepare to ride the streets of Lower Price Hill. Down Burns Street, along Evans to Gest Street. It’s a nice summer morning for a ride, but this one is not just for fun.

Some of the riders have clipped portable air monitors to their bikes or safety vests to capture real-time data about the quality of the air in the neighborhood.

The devices stream information about particles in the air, humidity, and temperature to a tablet carried by team leader Jaeydah Edwards. When the ride ends, she delivers the findings in decidedly nontechnical terms: “Right now, the air quality is bad.”

The numbers gathered will be added to a growing volume of information about air quality in this urban, Appalachian neighborhood, data gathered by Jaeydah’s employer, Groundwork Ohio River Valley, a not-for-profit dedicated to raising awareness about health and the environment in neighborhoods that have historically been neglected.

GORV’s home base is in Lower Price Hill, where its corps of youth and young adults have done most of their work. Here, that includes planting trees, helping to build a green roof on Oyler School, planting a pollinator garden, and importantly, measuring and documenting the impact of decades of environmental insults.

“There’s been a historic disinvestment there and a lack of protection,” says Sarah Kent, GORV’s executive director. “Companies that could have heavy pollutants were just allowed to take up residence next to actual residences, perpetuating a danger for those people.”

Lower Price Hill

Lower Price Hill’s environmental legacy dates back decades to at least the postwar industrial boom in the 1940s. Its people are on the low end of the income scale and they breathe a higher rate of toxic air than the rest of the city. Being poor, most residents have few options to move.

The average life expectancy in the neighborhood is only 63, a full 15 years less than the national average. That’s at least partly due to exposure to air pollution from cars, trucks, and trains. The neighborhood’s southern border is U.S. 50, a highway that sees thousands of vehicles a day. It eastern border is the Mill Creek, for decades a dumping ground for industrial waste. Just beyond that waterway is the Queensgate rail yard, one of the largest such facilities in the U.S., and filled with idling diesel locomotives and other equipment. The neighborhood is also home to the region’s largest wastewater treatment plant, where the odors from 100 million gallons a day being processed waft through the air.

While Lower Price Hill residents live with toxic air every day, the issue literally exploded into the public’s consciousness in 2004, when an old industrial recycling facility filled with leaky barrels containing remnants of toxic chemicals caught fire. The Queen City Barrel fire was an environmental catastrophe. Residents were advised to stay indoors, as the smoke plume from the inferno delivered benzene, toluene, xylene, and other toxins into the air. Those same chemicals were also found in water runoff that had collected in the streets and flowed into the sewers.

This is the environmental legacy that Groundwork’s Green Team, its high school youth program, and its Green Corps young adult workforce work to change. Its grassroots approach starts with residents and community organizations and asking what they need for a healthier sustainable neighborhood.

As the planet is slowly getting hotter, neighborhoods like Lower Price Hill are at risk. The community is old, with lots of narrow streets, aging industrial buildings, lots of concrete and blacktop. There’s not enough trees or grass to cool the air. As a result, the temperature on the sidewalks can be several degrees warmer than average. It’s a heat island. That can exacerbate asthma and heart disease, or cause people to stay indoors. Working with the community, Groundwork leaders drafted a climate resiliency plan for the neighborhood. To begin to minimize the heat island effect, Groundwork’s youth teams planted hundreds of trees in the neighborhood.

Groundwork teamed up with Cincinnati Public Schools in 2023 to install a green roof on Oyler School. Vegetation was planted and stormwater collection methods using native plants were built to collect rainwater in a sustainable way. The plants and water help cool the surrounding area. Green roofs also offer refuge for local insects and birds, and offer a way for urban dwellers to interact more with nature.

The teams recently completed a 1,600-square-foot pollinator garden at Evans Field, a Cincinnati Recreation Commission ball field and skate park. That was a collaboration with Civic Garden Center, Keep Cincinnati Beautiful, and B the Keeper, a local landscape designer that focuses on pollinator plants. Cincinnati brewery MadTree is a corporate partner.

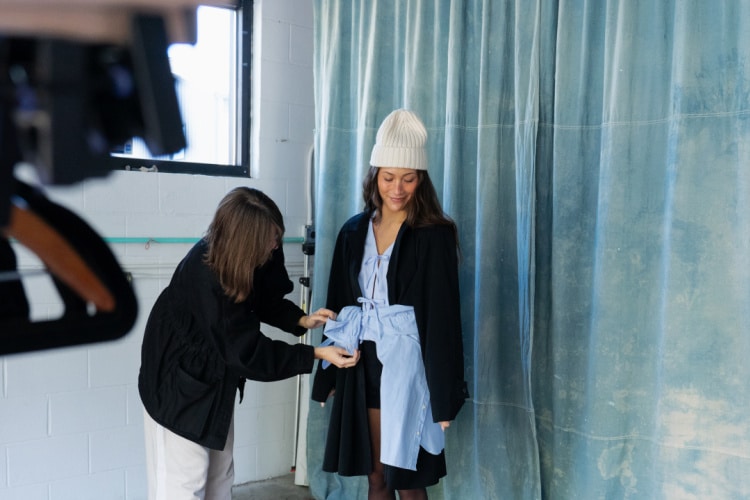

Ayva Dorris is a summer youth leader for Groundwork.

Groundwork’s larger purpose is to inspire a new generation of environmental leaders to continue the work of making neighborhoods greener and sustainable. Ayva Dorris is one of them. The 22-year-old is a summer youth team leader working to plant native species, remove invasive plants, and build a community garden. Much of her work this summer has been in Winton Hills, a neighborhood largely composed of a public housing complex that has its own history of environmental issues, bordering the Mill Creek, the Ivorydale industrial complex, and an old landfill.

Her work experience in those two neighborhoods should prepare her for a career in the field. “I went to school for environmental sustainability, and I have a pretty solid experience in intersection of environmental and racial justice,” she says. “And Groundwork is all about that.”

One of her team members is Isaiah Robinson, a 19-year-old who got involved in Groundwork through a community church. “They let me know about a summer program about plants and stuff,” he says. “I’m fascinated with plants, so I signed myself up.”

He and his friends from Winton Hills spent a Monday in Lower Price Hill taking air quality measurements, and building monitors to install around the neighborhood to measure the particulates in the air.

It can be valuable experience. “This gets them involved in their own community, lets them know that this could be a job for them,” Kent says. Staying with the program and joining Groundwork’s Green Corps for young adults can result in earning industry certifications, internships and jobs, sometimes with Groundwork’s community partners, such as the city of Cincinnati, Cincinnati Zoo, Hamilton County parks and others.

While Lower Price Hill has been a focus, other neighborhoods with histories of disinvestment have been locales for Groundwork’s efforts. It’s currently recruiting for a community advisory group in the West End. That will be a dozen or so community members who can provide insight into the neighborhood and start to create a community plan to improve climate resiliency there. That may include mapping where to plant trees, a community garden, a green roof, a cooling bus station, or whatever else they decide.

“Being able to see the problem and see that there are ways to challenge the problem empowers the group,” Kent says. “It allows them to be more involved in their community and then bring more neighbors in to make a change.”

Changing policies are a long-term goal too. For example, Groundwork was at the table when Cincinnati updated its Green Cincinnati Plan, the city’s guiding document for dealing with the effects of climate change. Youth spent hours at Green Cincinnati Plan meetings, contributing recommendations that were incorporated into the goals and actions aimed at making Cincinnati more climate resilient. Cincinnati City Council approved the plan in 2023.

This series, Health Justice in Action, is made possible with support from Interact for Health. To learn more about Interact for Health’s commitment to working with communities to advance health justice, please visit here.