Partner Partner Content Building a better environment

There isn’t a single solution to the challenges of greening our built environment but improving the sustainability of existing and future buildings can be done.

The built environment contributes more to carbon emissions (nearly 40%) and uses more energy (nearly 40%) than any other sector (according to the Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction).

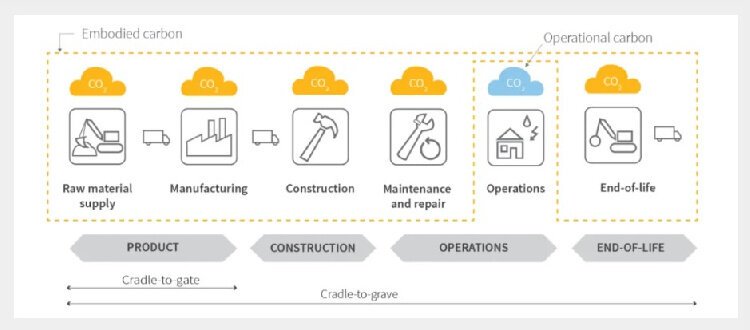

Before construction even starts, buildings impact the environment through harvesting raw materials (wood, clay, petroleum, etc.) and manufacturing of building products (lumber, bricks, shingles, concrete, etc.). Construction creates additional impact through clearing and preparing a site, transporting materials, equipment emissions, and job site waste. Once the building is completed, its operation – heating, cooling, electricity, water – contributes, as do the materials and equipment needed for maintenance and repair. After decades, maybe centuries, of use, a building is demolished, expending more energy and creating more waste.

Once upon a time, building construction used local materials and responded to the local climate. Builders used passive design strategies – orientation to the sun, location of shade or wind blocking trees, window size and location, wall thickness, roof pitch, etc. – to suit the weather. Industrialization and improved transportation gave builders more material options. Advances in central cooling and heating meant nearly anything could be built anywhere.

The shift away from designing for place is one of the most critical challenges with the built environment. Addressing climate change requires rethinking what is built and how its done, as well as the materials and energy buildings use.

Greening Buildings by Certification

The oil crisis of the 1970s prompted efforts to improve energy efficiency in our built environment but the deregulation of the 1980s slowed progress on these efforts. Sustainability issues returned to the forefront in the 1990s and have remained there as the impact of climate change becomes increasingly visible.

Today there are nearly a dozen certification programs including BREEAM, Energy Star, Fitwel, GreenGuard, LEED, Living Building Challenge, Phius, and WELL. Explaining the specific criteria of each would require a series of articles. But there are a couple you are more likely to experience in greater Cincinnati.

“LEED is the most recognized sustainable building certification in our industry,” said Christopher Hernandez, AIA with Process Plus. “It uses a scorecard system where buildings can earn points for meeting certain criteria in different impact categories.”

A LEED building might be ranked Certified, Silver, Gold, or Platinum based on the number of points it receives on the scorecard. Residential and commercial buildings can receive LEED certification.

The first Phius building in Cincinnati was completed late last year. Phius is also known as passive house, but any building type can be certified.

“Passive house has three requirements: extremely well insulated, airtight, and a mechanical fresh air ventilation system,” said Scott Hand, AIA with Trilobite Design. “Attaining these three elements uses as little energy as possible to maintain the comfort of the occupants.”

Unlike LEED which awards points for specific items, Phius looks at overall building construction and performance. Which means the insulation used could be anything from traditional fiberglass to sustainable haybales as long as the performance meets the criteria.

While LEED and Phius can technically be applied to any structure type, LEED can be cost prohibitive for small projects and Phius can be harder to achieve with large buildings.

The WELL Building Standard® and the newer Fitwel (originally developed by the Centers for Disease Control) focus on the health of the people who occupy buildings.

“WELL uses evidence-based design to explore the connection between buildings and the health and well-being of their occupants,” said Hernandez. “There are simple cost effective strategies that can be implemented such as offering active workstations, showcasing stairs at entrances to encourage their use or in a cafeteria promoting healthy food options and reducing access to processed foods to name a few.”

Incentivizing Green Building

Even with all these credentialling opportunities, of the over 111 million buildings in the United States, less than 200,000 buildings (only .12%) are certified through a green or sustainable accreditation program.

As good design practice, architects incorporate commonly used sustainable materials and systems whenever possible. But to implement more advanced sustainable strategies, architects need the client’s buy-in. The most environmentally friendly materials or technologies may carry a higher price tag. Credentialing also incurs a fee, which may be substantial. These costs can cut into the client’s profit.

“Implementing sustainable practices isn’t the issue, it’s getting the client to buy in,” said Chad Kohler, AIA, with Burgess & Niple. “Commercial clients frequently calculate the investment as marketing to encourage tenants and jobs, not for the greater good.”

Building owners, whether commercial or residential, are often looking at the return on their investment when considering green building; how much will it pay off and when. Those calculations vary wildly depending on the building type and size as well as the specific sustainable elements.

“The long term benefits are worth it,” said Hand. “Gas costs are never going to go down. Operating a passive house may cost half as much and it can be paired with solar to further reduce expenses.”

The new passive house in Cincinnati is 3,400 square feet with a monthly utility bill of $200. Meeting Phius criteria can also count toward other certifications.

At the federal level there are tax incentives to encourage sustainable building. State and local municipalities may also offer tax credits or property tax abatements for specific green credentials, materials, or processes. Historic tax credits, although not directly tied to sustainable design, do have an environmental impact.

Carl Elefante, FAIA coined the phrase “the greenest building is the one already exists.” And he’s right. Existing buildings have already “paid off” the energy used by their materials, manufacturing, and construction (embodied energy). Demolition and new construction requires significantly more energy consumption. But buildings that are 50, 100, or 200 years old often operate less efficiently than new construction.

“Existing buildings have largely been addressed as afterthought,” said Matthew Spangler, AIA, with Hixson. “We haven’t figured out a good way to infuse existing building stock with the same net sustainable outcomes as we do with new buildings. And keep in mind that going forward we’ll only ever have more existing building stock, not less.”

In 2009, the Over-the-Rhine Foundation released their Green Historic Study exploring whether existing buildings in that neighborhood (built in the nineteenth century) could be renovated to LEED standards. Their study showed it is possible.

Supply and Demand

In addition to the challenge cost may present to green building, access to appropriate materials and skilled contractors can also prove difficult for projects aiming for sustainability.

“LEED’s purpose is to stay out in front and act as a market-transformative instrument,” said Spangler. “UGSBC has been successful working with manufacturers to understand what is technically feasible, letting the market catch up, then pushing forward again. Over time, this cycle inherently moves design and construction down a more sustainable path, but it can be slow progress.”

As technology changes manufacturing, it also changes production of raw materials, which then evolves the thinking on what is, or isn’t, sustainable.

“Twenty years ago, wood wasn’t considered sustainable,” said Kohler. “But now, wood can be sustainably farmed and turned into mass timber for use in high-rise buildings. Which is more sustainable than concrete and steel.”

In addition to access to suitable materials and products, the labor market today makes it difficult to find contractors to build sustainable projects.

“For the passive house, we’re not using new technologies or materials, but the way they’re assembled is new,” said Hand.

Providing training and education to builders on new assemblies and technologies is essential, as is emphasizing the importance of choosing sustainable materials and products.

“Contractors are trying to be good fiscal agents for the client,” said Kohler. “When cheaper alternatives are available, they’ll choose those as a way to save costs.”

Architects can provide closed specifications on materials and equipment by stating “no substitutes” or include performance requirements to control the product choices.

“Integrated design, where all the stakeholders are on board from the beginning is best,” said Hernandez. “Owners, contractors and the design team are all part of the decision-making process, buy-in from all parties early in the process is key for success.”

Compelling Compliance

Perhaps the biggest issue with greening buildings is that sustainability is almost entirely optional. Developers and owners need to see value in green design and choose sustainability, even when it may cost more up front or impact their return on investment.

The International Code Council (ICC) creates a model building code, the International Building Code (IBC), updated every few years, which can be adopted in whole or in part by jurisdictions anywhere in the country.

“The IBC sets out guidance for how big, how tall, how many, types of materials, and building systems,” said Spangler. “Mechanical, fire, plumbing each have their own referenced codes. The energy code is also a referenced code. It tells you from a prescriptive or performance-based modeling standpoint, the specific metrics you’re required to meet based on your geographic location. The energy code has been the single biggest mandate to think more sustainably, specifically in the area of building energy consumption.”

The energy code is intended to drive down energy consumption. But, like the IBC, its adoption by state and local jurisdictions is optional. The most recent IBC was released in 2021. The State of Ohio last updated their building code in 2017, which references the 2015 IBC and the 2012 energy code putting the state nearly a decade behind the most recent standards.

The state of California adopted their own Green Building Standards Code (CALGreen) reduce greenhouse gasses. Application of that code helped reduce emissions from buildings by the equivalent of removing 12 million cars off the road annually. New York City has a requirement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from buildings by 40% by 2030. Building owners there are experimenting with carbon capture technologies in addition to converting gas systems to electric.

Including sustainable and energy conservation measures in the building code makes them required. When more efficient windows, vapor barriers, and insulation are required, it prompts manufacturers to focus on making those products instead of less sustainable options, which reduces their cost and makes green building more affordable.

The Solution

There isn’t a single solution to the challenges of greening our built environment. But this country has taken on systemic issues that were damaging our health and the environment before. Removing lead from paint and gasoline was going to destroy the automotive industry. It didn’t. Removing CFCs from aerosols to stop eroding the ozone layer was questioned as fake science. It wasn’t. Banning smoking in public spaces was going to put restaurants out of business. It didn’t.

Improving the sustainability of our existing and future buildings can be done. It will take pressure from individual citizens and corporations at all levels of government—local, state, and national—to have a measurable impact.

While advocating and waiting for building codes, incentives, manufacturing, and construction to catch up, everyone can try to reduce the energy impact of their homes, apartments, and offices, whether that’s putting plastic over windows in the winter, planting shade trees, switching out lightbulbs, or setting the thermostat differently. Individuals can also “vote” with their wallets by patronizing businesses with sustainable practices. Most importantly everyone can educate themselves about these issues and remind others that good, sustainable design matters.

The series, Architecture Matters, is supported by AIA Cincinnati. Learn more at aiacincinnati.org.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the American Institute of Architects or the members of AIA Cincinnati.