An early adapter of women’s voting rights, Ohio lags behind nation in women’s political leadership

Since the ratification of the 19th Amendment 100 years ago, women have made great strides in the political arena. But there's still a long way to go.

Jo Ann Davidson was first female Speaker of the House in the Ohio General Assembly, serving from 1995 to 2000. Since then, no woman in Ohio has ascended to the same position of power.

Why is that?

During the upcoming centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which gave women in America the right to vote, both genders will be discussing how far women have come as political leaders and how far they still have to go.

Nationally, more women were elected to Congress in 2018 than have ever served before. Nearly one in four members of the U.S. House of Representatives (23.4 percent) are now women. The same goes for the U.S. Senate, where 25 women are now among the 100 senators from all 50 states. And let’s not forget that the first woman to run for U.S. President, Hillary Clinton, won the majority of votes nationally in 2016 but failed to win the majority of Electoral College votes that would have secured her the office.

That’s all good news for women. But keep in mind that women make up the majority of all voters in the U.S. — 51 percent. And when you look at party affiliation, Democrats are far more represented by women than Republicans — by a ratio of nearly 7 to 1 in the House and 3 to 1 in the Senate.

One explanation for the difference, of course, is that Democrats value political diversity more than Republicans. One in three Republicans believes there are too few women in political office while eight in 10 Democrats think so, according to the Pew Research Center.

Ohio has not fared as well as much of the country in terms of women’s political leadership. In 2018, Ohio scored below the national average in the percentage of women serving in the state legislature — 22 percent compared to 25.4 percent for all states.

At the congressional level, three of Ohio’s 16 representatives are women, again lower than the national average. But as U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur of Toledo, the longest-serving woman in congressional history, point outs, it wasn’t for lack of trying among Democrats.

Democratic women contested incumbent Republican men in the 2018 election in three districts in Ohio but failed to win in any of them.

“It was probably the highest number of women (congressional candidates) in Ohio’s history,” Kaptur says. “But now that Ohio is terribly gerrymandered, for someone to win would have been an incredible achievement.”

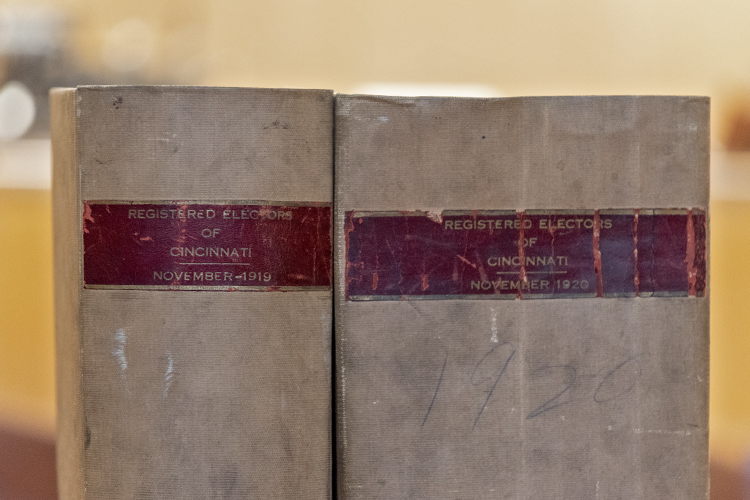

For Ohio to trail the rest of the country in women’s political leadership is somewhat surprising given that it approved the failed Equal Rights Amendment in 1974 and was the sixth state to ratify the 19th Amendment on June 16, 1919 — less than two weeks after Congress approved the measure on June 4 of that year. Fourteen months later, on August 18, 1920, Tennessee was the last of 36 states needed to ratify the amendment, making it the law of the land in time for the 1920 presidential election.

Davidson believes there are factors holding back women in Ohio that cross political lines. The continuing absence of women in the top positions of political power in Ohio led her to launch the Ohio Leadership Institute in 2002, an organization that recruits, encourages, and trains Republican women in Ohio to run for office.

“There are three big issues,” Davidson says. “The number one issue is their lack of self-confidence. Number two is that they want to be asked (to run for office). Number three is that they are not risk takers.”

“One woman (we talked to) who would have made a wonderful state representative told us, ‘If you can guarantee I’ll win, I’ll run,’” Davidson recalls. “But, obviously, there are no guarantees in politics.”

Davidson calls herself “lucky” that she was defeated the first time she ran for office — an unsuccessful bid for Reynoldsburg City Council in 1965. “What you learn from being defeated teaches you a lot about being a candidate and mistakes that you made,” she says. “But when you suggest that someone be on the ballot, that’s not the most convincing argument.”

The women who fought for the right to vote in America met failure and defeat for decades before reaching their goal in 1920. And like any mass political movement, there were internal battles and divisions over goals and tactics along the way.

The biggest split in the movement came in 1869 between white and black suffragists over who should get the vote first — black men or white women. At an 1869 American Equal Rights Association meeting, white suffragist leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton “decried the possibility that white women would be made into the political subordinates of black men who were ‘unwashed’ and ‘fresh from the slave plantations of the South,’” according to historian Martha S. Jones. Stanton, an abolitionist, was railing against the 15th Amendment, which gave men the vote in 1870 without regard to “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

At that same 1869 meeting, black suffragist Francis Ellen Watkins Harper, a teacher, poet, and anti-slavery activist, said: “If the nation could handle one question, she would not have the black woman put a single straw in the way, if only the men of the race could obtain what they wanted.”

The debate led to a deep schism in the suffrage movement, with women dividing their efforts into the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), led by Lucy Stone, who wanted universal suffrage, and the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by Anthony and Stanton.

Many white female leaders were worried that an endorsement of the black vote would derail efforts to win over Southern states in the fight for women’s suffrage, says Megan Wood, director of cultural resources for Ohio History Connection, the state’s historical society. “But it’s also true that (many) women in the suffrage movement also reflected the broader thinking in the late 19th century, and that included the structural racism of the times.”

Women’s suffrage was also complicated by another heated issue at the time: the possibility of prohibition. There was much overlap between the women’s temperance movement to outlaw alcohol and the suffrage movement to gain women the right to vote. That’s a big reason Cincinnati, a major brewing and distilling center, was a stronghold in Ohio against the 19th Amendment, says Katherine Durack, a former Miami University professor who maintains a website, Suffrage in Stitches, about the role of domestic arts in advancing the suffrage movement.

“The fear in Cincinnati was that, if women got the right to vote, they’re going to take away your right to drink and even your right to smoke,” Durack says. “The whole idea was to frighten people if women got political power.”

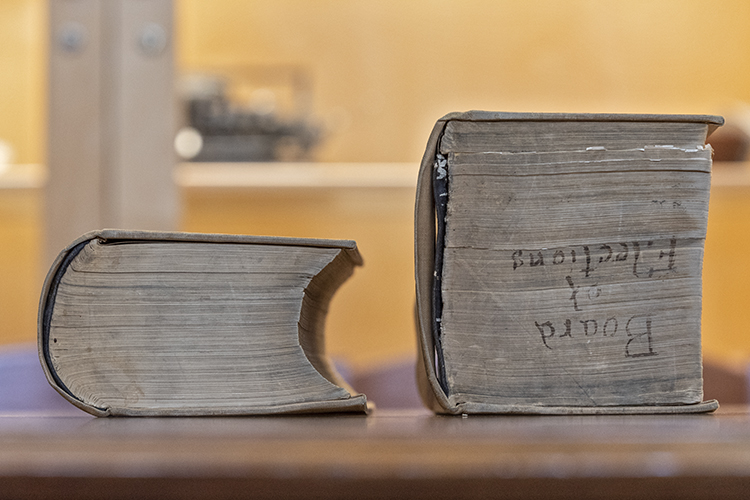

Unlike the pioneering Western states of Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, Washington, and California, Ohio did not allow women to vote in statewide elections before 1920. But many local municipalities under Ohio’s home rule provisions did allow women to vote in local elections, particularly for school board, which was seen as a “natural sphere” of influence for women at the time, Wood says.

Ohio was a center of much national attention in ratifying the 19th Amendment, not only because the state was an early adopter but also because both major presidential candidates leading up to the 1920 election — Republican Warren G. Harding and Democrat James M. Cox — were from Ohio.

“There was a lot of pressure on the two candidates to take a stand on the 19th Amendment, but both were reticent,” Wood says.

As Woods points out, endorsing the 19th Amendment was a risky proposition for both candidates. It would mean alienating many male voters and losing support in those states that didn’t ratify the amendment. But opposing the amendment was even riskier. If it passed, the candidate would face the wrath of the newly enfranchised female voters, who made up 51 percent of the population.

The likelihood that the 19th Amendment would be passed before the 1920 presidential election led to the formation of the League of Women Voters of Ohio in May 1920, says Jen Miller, executive director of today’s organization. The league’s founding mission is still the same today: helping new voters navigate the process and providing non-partisan information on issues and candidates to inform their votes.

2020 will mark not only the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, but also the founding of the League of Women Voters “and the hundredth anniversary of elections that women have voted in,” Miller says. “We’re hoping that women, especially young women, will be inspired by this momentous occasion and take their right to vote seriously.”

Support for Ohio Civics Essential is provided by a strategic grant from the Ohio State Bar Foundation to improve civics knowledge of Ohio adults.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the Ohio State Bar Foundation.