Getting Behind The Lens With Michael Wilson

You may not know photographer Michael Wilson, but if you own an album by The Replacements, Lyle Lovett, or Emmylou Harris, you’ve undoubtedly seen his gorgeous black and white portraits. Wilson, who lives on Cincinnati’s west side, has eschewed the limelight of more celebrated photographers in deference of his subjects, both famous and not so famous, and created a unique style that is highly sought-after by artists all over the world.

While other successful artists born and raised in Cincinnati sometimes leave the Queen City for the bright lights and job opportunities of larger cities, photographer Michael Wilson has never moved away. And though you may not know Wilson, there’s little doubt that you’ve seen his work. For 30 years Wilson has been responsible for portrait and album covers as diverse as Lyle Lovett to The Replacements iconic All Shook Down cover shot in Newport, Ky.

While other successful artists born and raised in Cincinnati sometimes leave the Queen City for the bright lights and job opportunities of larger cities, photographer Michael Wilson has never moved away. And though you may not know Wilson, there’s little doubt that you’ve seen his work. For 30 years Wilson has been responsible for portrait and album covers as diverse as Lyle Lovett to The Replacements iconic All Shook Down cover shot in Newport, Ky.

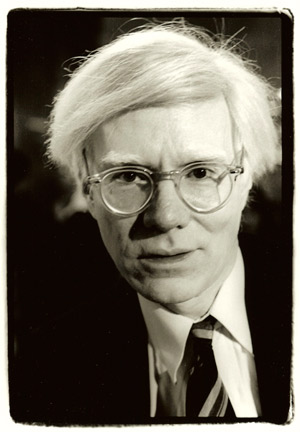

While Wilson’s professional and private work spans a broad range of subjects and styles, his work in the in the music industry is nearly ubiquitous and is certainly his most popular work. Among the artists Wilson has photographed: Lyle Lovett, Emmylou Harris, David Byrne, Philip Glass, B.B. King, and Randy Newman. Portraiture is his strong suit- especially portraits of musicians.

To get an idea of Wilson’s popularity and style, you need only look at the cover photographs for Lyle Lovett’s CD, Step Inside This House; (in which Wilson not only shot the cover, but numerous portraits of the Texas singer-songwriters Lovett covers on the disc); or the covers for Emmy Lou Harris’ Red Dirt Girl; or Buddy Miller’s Cruel Moon.

To get an idea of Wilson’s popularity and style, you need only look at the cover photographs for Lyle Lovett’s CD, Step Inside This House; (in which Wilson not only shot the cover, but numerous portraits of the Texas singer-songwriters Lovett covers on the disc); or the covers for Emmy Lou Harris’ Red Dirt Girl; or Buddy Miller’s Cruel Moon.

Despite the popularity of his work Wilson is not a household name even in his home town. Some of this anonymity is due, undoubtedly, to the fact that Wilson is, a modest, humble old school Cincinnatian. Born in 1959 in Norwood, he lives in Price Hill with his spouse of 25 years, Marilyn, and three children. Like a true westsider, Wilson is not given to showmanship; in fact, he’s humble and soft spoken nearly to the point of being shy. He’s one of those guys who simply isn’t comfortable talking about himself. This back-story is worth discussing because Michael Wilson’s humility, his down to earth workman-like approach to his craft is one of the many things that sets him apart from other artists.

Wilson did not aspire to become a photographer. At Norwood High School his friends were musicians. He participated in band playing the french horn and worked to save enough money to buy his own horn. But his interest in buying a horn dissipated, leaving him with a small stack of cash he felt obligated to spend. Recalling a friend’s interest in photography, he bought a camera. This is not to say that he has ever lost interest in music. It’s no coincidence that Michael Wilson has made his bones shooting musicians. “Music, ” Wilson says, “has always been my main, chosen diversion. Music has always been special.”

Wilson’s camera purchase coincided with his graduation from Norwood High School. At that time, a fledgling Northern Kentucky University was offering a full academic scholarship to local high schools in an effort to establish the University’s name in the region. The scholarship was duly offered to a number of students at Norwood, none of whom accepted the honor. On his last day of school, Wilson was called to the principal’s office where he was told that he was being awarded a full academic scholarship, to NKU, despite “the fact that I had failed math the year before,” he says.

Upon presenting himself to NKU, Wilson was asked to declare a subject of study. He had no idea. Finally, Wilson offered that he had just purchased a camera and suddenly, Michael Wilson was a fine arts student studying photography.

Upon presenting himself to NKU, Wilson was asked to declare a subject of study. He had no idea. Finally, Wilson offered that he had just purchased a camera and suddenly, Michael Wilson was a fine arts student studying photography.

Once at NKU, Wilson fell under the spell of what he terms, “the usual suspects: Walker Evans, Robert Frank; and Bill Brandt, among others.” He began to study and shoot in earnest. He ultimately began shooting freelance several years after graduating from NKU. Wilson circular foray into the world of photography also foreshadowed his subsequent unique approach to the photographic process.

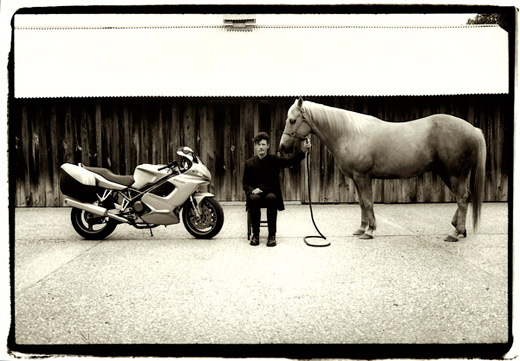

Wilson’s approach to his work is a unique, and unlikely, blend of chance and precision, and is, in many ways, a study in paradox. When Wilson goes out into the field he leaves a lot to chance – literally trusting fate to provide him with a studio in which to work, and backgrounds against which to shoot his subjects. Wilson shoots what he finds – meaning that he does not travel as do most photographers doing similar work, with either lights or backgrounds. Nor does he shoot subjects in the studio against preconstructed backgrounds or sets. In many ways, a hunter, a photo-journalist in the very best sense

What Wilson does do is to travel to a given location- New York, London; wherever, and then search out an appropriate setting in which to shoot his subject. He normally does not know, for instance, when he travels to Nashville to shoot musician Rodney Crowell, or to Austin to shoot Lyle Lovett, that he will be shooting a portrait of Crowell ascending a steep staircase leading to an open window which is flooded with bright, natural light. Rather, he’ll simply arrive on the scene and work with what the world gives him.

What Wilson does do is to travel to a given location- New York, London; wherever, and then search out an appropriate setting in which to shoot his subject. He normally does not know, for instance, when he travels to Nashville to shoot musician Rodney Crowell, or to Austin to shoot Lyle Lovett, that he will be shooting a portrait of Crowell ascending a steep staircase leading to an open window which is flooded with bright, natural light. Rather, he’ll simply arrive on the scene and work with what the world gives him.

It’s an approach that can drive art directors mad, and make some artists nervous. To Wilson, however, it’s an organic way to work and one that ultimately doesn’t entail all that much risk.

“It’s an interesting world and you really don’t have to scratch that hard to find somewhere worth shooting,” Wilson notes.

That he leaves to so much to fate is compelling given that the backgrounds against which Wilson works are often as interesting as the subjects. This is not to say that this process is foolproof. Wilson notes that, “to the extent that my photos do sometimes fall flat, those problems can be traced to a lack of preparation, a lack of scouting out a set ahead of time.”

In a world of digital color photography manipulated by Photoshop, Wilson still labors in a darkroom working with black and white film. He eschews digital stamping for the time honored traditions of working with filters, burning and dodging. Why film in a digital world? Wilson cites several reasons for his preference.

In a world of digital color photography manipulated by Photoshop, Wilson still labors in a darkroom working with black and white film. He eschews digital stamping for the time honored traditions of working with filters, burning and dodging. Why film in a digital world? Wilson cites several reasons for his preference.

“The first is simply familiarity – I take pleasure in a process I’ve done for thirty years.” Secondly, he says, “I like that film limits the amount of possibility – that the process forces limits on the number of photographs to be taken of a given situation. Film insists on the photographer narrowing their vision. I find myself exhausted at the number of photos shot over the years. Digital says, ‘it’s all possibilities- keep choosing,’ but the more analog the system, the more you’ve got to make a decision.”

In similar fashion, Wilson prefers black and white over color film because “there is a distillation that happens when the world is drained of color- and that distillation can be important- it’s also about choices.” Whether working in the field, or the darkroom, Wilson’s methods are precise. He rolls his own canisters of film prior to shooting, ensuring that each roll contains thirty, not thirty-six, exposures (because thirty exposures fit better into a standard negative sleeve). He also develops the exposed black and white film himself, according to archival standards. Subsequent to developing the film, Wilson is equally particular about creating his prints.

Such exactitude yields compelling results. Wilson’s photographs are rich with contrast, they feature dark inky blacks against pearly whites. By combining his spontaneous photo journalistic approach to setting and shooting, and such exacting standards in creating his prints, Wilson ultimately tells stories in a time honored manner not often encountered today. His work is not just another image in a world flooded with images. Rather, Wilson’s photography is art that boils subjects down to their monochromatic essence.

Such exactitude yields compelling results. Wilson’s photographs are rich with contrast, they feature dark inky blacks against pearly whites. By combining his spontaneous photo journalistic approach to setting and shooting, and such exacting standards in creating his prints, Wilson ultimately tells stories in a time honored manner not often encountered today. His work is not just another image in a world flooded with images. Rather, Wilson’s photography is art that boils subjects down to their monochromatic essence.

This is why Wilsons’s work is not only appreciated by musicians, art directors and the public, but also praised by fellow photographers. Cincinnati photographer and sound engineer John Curley calls Wilson, “probably the best photographer in Cincinnati,”- no small praise in a city full of accomplished photographers. Lifetime photo-journalist, and Taft Museum Duncan Artist, Melvin Grier calls Wilson’s work “meticulous.”

“I appreciate that he doesn’t clutter things up. There are no distractions in his photographs, they speak for themselves. Nothing gets between himself and his subject and their relationship. The subject in his photograph is the subject. He doesn’t take away from the subject by interjecting all those other things into his photography,” Grier says.

For his part, Michael Wilson is happy just to keep going. He reflects on his web site that, “Twenty-some years now into the adventure, much has changed – both in and out of photography. What hasn’t changed, however, is that strong pictures still resonate and compel and I am grateful to still be in search of them.”

Photography by Michael Wilson

Lyle Lovett

Michael Wilson (by Scott Beseler)

Jackie Greene

David Byrne

The Black Keys

Andy Warhol