Walnut Hills reimagines future of food security in wake of Kroger departure

Kroger will exit Walnut Hills next month, leaving a sizable gap in the community's food resources. Soapbox looks at what neighborhood leaders are doing, both short- and long-term, to address the issue.

On Dec. 2, Walnut Hills residents woke to the news that their neighborhood Kroger will close its doors for good in early March.

The announcement comes as a blow to longtime residents who, despite considerable economic growth in parts of Walnut Hills over the last decade, have seen neighborhood amenities disappear one after another. Now, with Kroger’s departure, one of their most basic needs — access to food — is being threatened.

The neighborhood Kroger store opened in 1983 and has been in limbo for years. Leaders have been proactively engaged in conversations over what to do if, or when, the store finally closed. Now, a date is set and residents must work together to find a viable and equitable solution to the crisis. Without a plan, food security will become one more thing that divides the neighborhood’s most disenfranchised residents from those with access to amenities beyond Walnut Hills.

Thinking outside the ‘big box’ for food

In the first half of the 20th century, the main corridors of Walnut Hills were lined with the types of specialty shops where Americans typically bought groceries and household goods. These mixed-use business districts offered a more personalized shopping experience and helped bolster the local economy.

The rise of big-box retailers and one-stop grocers coincided with the suburban sprawl of the late 1900s and the dismantling of traditional business districts. Today, Cincinnati’s own Kroger Company has grown to become one of the nation’s largest retail chains. Over the last 30 years, as Walnut Hills saw many locally owned businesses shuttered, the neighborhood Kroger remained a reliable, convenient place for residents to shop.

But with neighborhood demographics in constant flux, the Walnut Hills Kroger has long been vulnerable. Grassroots community groups have worked to boost the store’s profitability, but to no avail. According to an official statement from Kroger, the Walnut Hills store has had only one profitable year since 1991 and has lost $4.9 million in the past six years alone.

The completion of a new $25 million University Plaza store in neighboring Corryville (near University of Cincinnati) further solidified Kroger’s decision to close the Walnut Hills location.

In an effort to soften the blow, Kroger is helping broker stop-gap solutions for Walnut Hills residents. For the next few months, a partnership with Metro will supply Kroger shoppers with bus tokens. And for the next year, Cincinnati Area Senior Services will likely provide transportation to and from the new Kroger in Corryville for senior citizens and disabled residents. In addition, all 81 of the store’s current employees are being offered positions at other Kroger stores.

Equitable solutions an oasis in the new food desert

The new University Plaza store is more than twice the size of the Walnut Hills store and will include a drive-thru pharmacy, Starbucks, natural foods section and more. It’s also less than two miles from the center of Walnut Hills and, in many ways, a vast improvement from the old, failing location.

The situation, however, is much more complicated for the neighborhood’s most vulnerable residents.

When Kroger closes next month, much of Walnut Hills will officially become a “food desert” — defined as a community in which residents have no full-service grocery store within one mile.

The situation poses more of an inconvenience than a threat for wealthier areas like East Walnut Hills, where a majority of residents have access to private transportation and costlier food-delivery services. Food deserts largely threaten low-income communities where fewer residents own vehicles and where there maybe be a disproportionate number of disabled or elderly residents.

Other food deserts exist across Cincinnati: parts of Avondale, Kennedy Heights, College Hill, Bond Hill and Evanston are a few examples. In such communities, residents become dependent on overpriced convenience stores, fast food and discount outlets like Family Dollar. Healthy food options are limited and fresh produce is scarce.

Further complicating matters, once a large grocer moves out, it’s often difficult to entice a new one to take its place. In College Hill, for example, a former Kroger stood vacant for more than 10 years, a magnet for blight and crime, before the community managed to secure its demolition in 2014. The lot is still empty today.

The Walnut Hills Redevelopment Foundation is managing much of the neighborhood’s current economic growth. In an effort to tackle the Kroger issue head on, the WHRF is putting short-term solutions into place, while formulating a collaborative plan for

long-term residential food security.

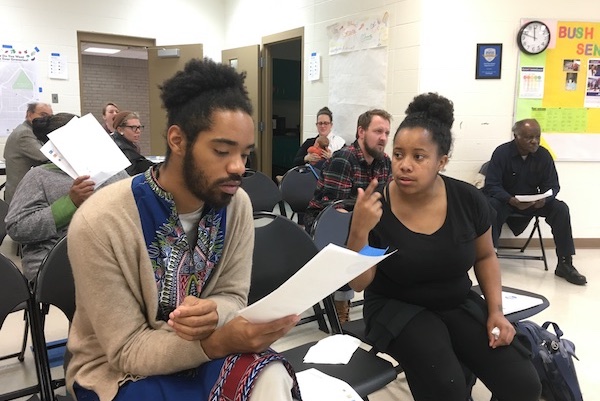

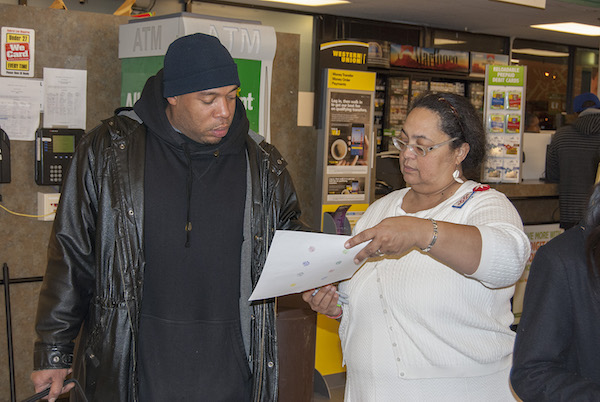

To that end, WHRF employee Gary Dangel is tasked with engaging residents to answer one simple question: How do you want to get your groceries?

Dangel works to engage people from every diverse corner of Walnut Hills through meetings, surveys and door-to-door canvassing. That input will factor into the choices WHRF makes for places like Peebles Corner, where 50,000 square feet of commercial space is undergoing renovation. The existing Kroger lot and building could be available for lease or development as early as next year. An equitable solution, he says, will be something that is accessible, and desirable, for all residents.

“As the neighborhood improves, we want the lives of the people that live here to improve as well,” Dangel says. “We want the people who have lived here and kept the neighborhood strong for the past 50 or 60 years to stay here. They are the backbone, the fabric, of the neighborhood.”

While bringing another large grocer into the neighborhood seems like an obvious solution, that could take years. In the meantime, the community is exploring more immediately scalable options, such as farmers markets, food hubs, grocery delivery services and community-supported agriculture.

Dangel says many residents are interested in bringing back specialty stores in lieu of a large, one-stop grocery. They claim the local economy would benefit and the shopping experience would bring residents together for daily interaction.

“We can take this situation and turn it into an opportunity to build something innovative, something that will also attract people from other neighborhoods,” Dangel says. “If we can develop something that’s creative and people see additional value beyond just buying their groceries for the week, we can consider that a success.”

Community engagement takes center stage in new chapter

When facing a serious question like how to tackle food insecurity, it’s natural for many residents to vacillate between skepticism and hope.

Mona Jenkins is one such resident. A trip to the neighborhood store, she says, is an opportunity to see neighbors and touch base about community issues. Losing the store means losing that touch point, that neighborhood “third place.”

“It’s not just about the food,” Jenkins says. “It’s about community.” She believes that in order for any new initiative to be successful, there must be buy-in, especially from low-income, minority and elderly or disabled residents. They are the ones who are most vulnerable to changes in their surroundings.

“When you get community input, you get community buy-in,” she says. “Bottom line, it has to be about what the community wants or else you can end up making changes that don’t work.

Walnut Hills resident and WHRF board president Christina Brown considers it her job to hold the foundation accountable to their mission of equitable development. As the Walnut Hills community and WHRF move forward, Brown wants to maintain checks and balances because, she says, “Hindsight is always 20/20.”

Brown explains, “I think the most important part is to practice humility in engagement because there are so many people who have been denied opportunities and resources for as long as they’ve been here. We have to acknowledge that some people are just fed up. I’m fed up. I go to Oakley and can see seven different grocery stores from one parking lot. Unfortunately, (Walnut Hills residents) have to fight for even the basic necessities.”

Brown echoes Jenkins, saying this is about more than just food. “How do we not further demoralize people?” she asks. “How can we be intentional about engaging folks who have been historically uninvited or ignored?”

Dangel believes the neighborhood is up to the task. “I think what’s exciting is the opportunity to build something that could be a model for other urban neighborhoods that are experiencing food insecurity and showing how you can solve that problem in an equitable way,” he says. “But that’s a big challenge. That’s a tall order to fill.”

On The Ground in Walnut Hills is underwritten by Place Matters partners LISC and United Way and the neighborhood nonprofit the Walnut Hills Redevelopment Foundation, who are collectively working together for community transformation. Additional support is provided by development partners Neyer Properties and CASTO. Data and analysis is provided by The Economics Center. Prestige AV and Creative Services is Soapbox’s official technology partner.