Little Free Libraries spread books and happiness

These “street libraries” help build community, boost literacy, and make people smile.

The first Little Free Library started when a man in Wisconsin decided to honor his late mom by building a small box for exchanging books in his front yard. That man was Todd H. Bol, who went on to build more mini-libraries, eventually co-founding the Little Free Library nonprofit organization that has led to more than 165 million books being shared across the globe.

What began as one little book exchange in 2009 has turned into a book-sharing movement that today features more than 100,000 Little Free Libraries in all 50 states and 108 countries.

As the “take a book, share a book” exchanges started to spread outside of Wisconsin, avid readers in the Queen City took notice. Today Greater Cincinnati is home to more than 200 Little Free Libraries.

The concept is simple: You can take a book, leave a book, or do both. Books don’t have to be returned to the library they were taken from, but contributing to the libraries helps keep the stock rotating and the sharing going. Anyone can start a Little Free Library.

Building stronger communities

Each registered Little Free Library receives a charter number. The lower the number, the longer the library has been around. Maggie Gieseke of Hyde Park is proud to hold charter #900. She heard about Todd Bol’s initiative on NPR in 2010. She was intrigued by the idea and ended up ordering a library (LFL sells them and also provides DIY building plans on their website). Weeks later, the Giesekes installed one of the first Little Free Libraries in Cincinnati at their corner home.

The family has since replaced that original with two libraries — one for adults, and one just for kids.

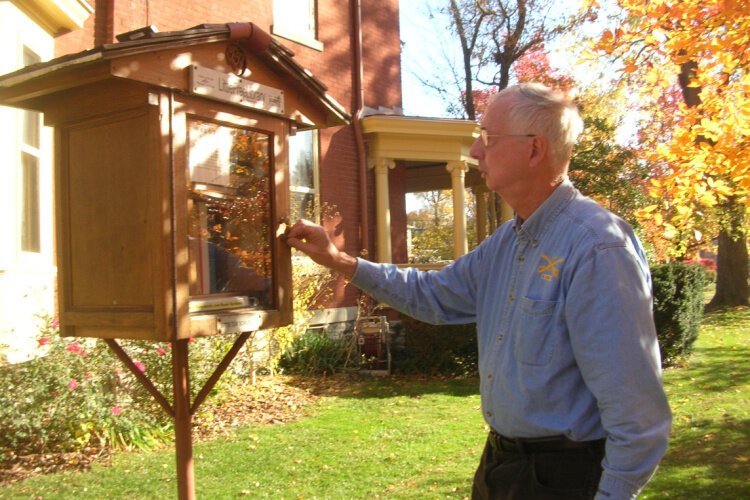

Part of the charm of Little Free Libraries is their individual designs. Some people buy them pre-made, others build them, while others repurpose structures such as old newspaper boxes. Bill Dean of Westwood (charter #19336) erected his Little Free Library at his home after his wife saw one in Akron.

“It’s made from quarter sawn white oak left over from my project to build kitchen cabinets in our historic house,” says Dean, who also stewards a Little Free Library at his church. (The term steward is used for those who manage these book-sharing boxes.)

Regardless of their look, the power behind them, their stewards say, is how they bring communities together. They spark conversation among neighbors and get people talking who may not have met otherwise. Dean says his library plus a bench he installed nearby have become “a literary oasis” for his neighborhood.

That sense of community is what motivated Todd Bol. When he saw what that first library did for his own neighborhood, he aspired to help build stronger communities elsewhere and get books into as many hands as possible.

Expanding access to books

Trina Carter stewards a Little Free Library in Lincoln Heights. She set hers up when her son got to high school. Lincoln Heights does not have a public library of its own, so its residents use those in bordering neighborhoods. But her son found he couldn’t check out books from his summer reading list because they were restricted for borrowing by students who were residents of the neighborhoods where the high schools are located.

Carter, who is a school librarian, took matters into her own hands for students living in Lincoln Heights. She chartered a Little Free Library (#35735) and placed it in front of her home. “Every year I look at the summer reading lists and then I go find those books and stock my library with them,” Carter said.

Increasing access to books is a cornerstone of the Little Free Library organization. They work to promote literacy and penetrate book deserts, which exist in many high-poverty communities.

Locally the Literacy Network of Greater Cincinnati hopped on board with this idea, launching an outreach program that has been installing Little Free Libraries as a way to help provide books especially for children in low-income families. To date, LNGC has placed nearly 90 Little Free Libraries at area parks, schools, community centers and places of worship with plans for more to come.

“Whether the books in the Little Free Libraries are helping to teach a child or adult to read, allow the reader to ‘escape’ in the book during this stressful time, or simply put a smile on a child’s face when they get a book from the library, we are proud to provide the Little Free Libraries throughout the community,” says Michelle Otten Guenther, LNGC’s president.

2020 changes for Little Free Libraries

Bol passed away in 2018, but his legacy lives on in ways even he likely did not imagine. During the COVID-19 shutdowns earlier this year, some stewards shifted their libraries for use as pantries for food and school supplies.

After the social unrest following George Floyd’s death at the hands of a police officer in late May, Gieseke made a pointed effort to offer books by diverse authors and with characters of color in both of her libraries.

“I felt limited as to what I could do to make a difference, but I knew I could do something,” Gieseke says. “I thought by featuring books that made a difference in my way of thinking, maybe they would be able to reach other people in the magical way of connection that books offer.”

The first books on racial inequality she stocked were snatched up quickly and she continues this effort today.

Behind the scenes

So what’s it like to be an LFL steward? “Everything about Little Free Libraries is pretty awesome,” says Kate Westrich, whose Little Blue House Library (yes, you can name your book exchange) stands in front of her home in Clifton. “Every time I see anyone visiting the library, it makes me smile.”

She sporadically checks on her stock. When she first installed her library (charter #75890), she tended to it daily. But she soon found, “My library is most successful when it’s untidy. In fact, when I load it up with books, I knock a few over before shutting the door. It seems to help.”

Some stewards buy books to stock in their libraries. Others simply let a natural give-and-take occur. Many say that neighbors often contribute by leaving bags of books on their front porches. Bill Dean’s neighborhood bookstore, Duttenhofer’s Books, routinely provides him with a supply that he uses to fill his Little Free Library, as well as others around the city. (One steward referred to this loading up of libraries as “book bombing.”) Dean uses LFL’s online map to find other local registered Little Free Libraries.

Believe it or not, most books do eventually get taken — fiction, nonfiction, historical, how-to, fantasy, romance, you name it. You never know what you’re going to discover when you open a Little Free Library, and that’s all part of the fun.

“I love the idea of people finding those little happy surprises,” said Carter.

I’m pretty sure anyone who’s ever peered into a Little Free Library agrees.

Contribute to the movement. Learn more about:

· Little Free Library’s Action Book Club, which combines reading and community service

· The literacy crisis in America

· Donating gently used children’s and young adult books for the Literacy Network of Greater Cincinnati’s Little Free Libraries