Agreeing to disagree: How can we put civility back into civic discourse?

Ohio groups are trying to turn the heat down on political discussion and find the ability to compromise that once made America and its political system a model for the world.

This story was first published on March 17, 2020. The author of this feature, Jim DeBrosse, was the lead writer for the first two years of a 3-year project called “Ohio Civics Essential.” Find the entire series here.

Posting a political comment on social media these days is like stepping into a verbal minefield. It can bring out anonymous “trolls” looking to insult, ridicule, or berate. Or lead to a heated exchange between “friends” that fails to inform, only inflame. In the worst case, it can even generate threats of retribution or violence.

No wonder the most recent national survey by KRC research, “Civility in America 2019: Solutions for Tomorrow,” found that more than nine in ten Americans (93 %) believe there’s a civility problem in the country, with 63 % blaming social media as a contributing factor.

But experts say there’s plenty of blame to go around.

“Some of it is absolutely the fault of intense ideological groups that support both political parties by drawing them more toward the extremes,” says Herb Asher, a professor emeritus of political science at Ohio State University. “It’s also gerrymandering of (congressional) districts because we end up with candidates that are more extreme. It’s the media — radio shock jocks, cable TV slanting the news, and all the social media that make it really easy to be obnoxious and mean and do it anonymously. It’s everything!”

Rob Baker, a professor of political science at Wittenberg University, says the problem is no longer just political, it’s become tribal in nature. “We’ve sorted ourselves geographically and ideologically into two separate parties, much more than ever before,” he says. “The conservative Democrats in the South are now Republicans and the liberal Republicans have all gone over to the Democrats.”

The result is that the country has been divided into two tribes — a term in behavioral psychology that, according to Baker, means: “We now have an in-group and an out-group and we want to protect our own tribe no matter what.” The emergence of social media has reinforced that tribalism because “we’re hanging out in echo chambers” with like-minded people who confirm our biases and “look at members of the other tribe as idiots and enemies.”

There are, however, groups nationally and in Ohio trying to turn the heat down on political discussion (See the sidebar to this story) and to find the ability to compromise that once made America and its political system a model for the world.

During the general election of 2012, The Akron Beacon Journal launched a community-wide project on civility “trying to understand why everybody is so mad at each other,” says Doug Oplinger, the newspaper’s former managing editor.

The Beacon Journal made a startling discovery after listening in on 25 focus groups of community members and readers who were asked what they thought had gone wrong with the election process. “In every one of them, they blamed the media,” Oplinger says. “We said, ‘No, we’re just reporting what’s going on.’ Afterward, we realized, whoa, we better pay attention because this is what people believe.”

Oplinger consulted with the National Institute for Civil Discourse, where a staff member agreed with the assessment of the focus groups. “She said, ‘They’re right. All you do is report what Republicans say and what Democrats says, and you don’t report what people say.’”

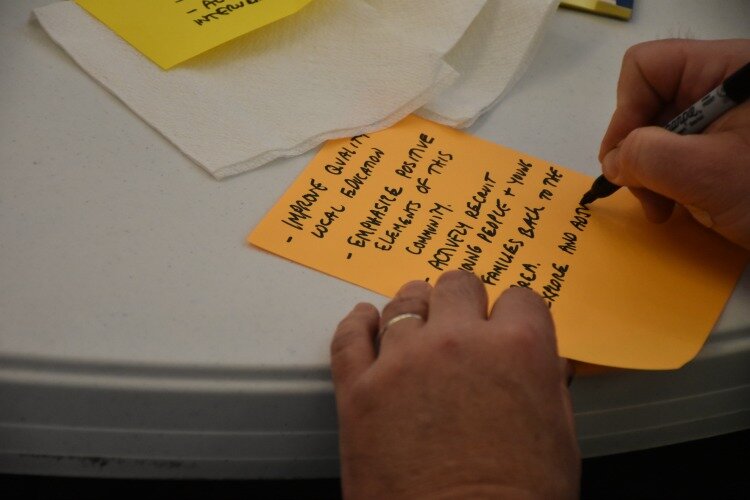

Oplinger decided it was time to launch Your Voice Ohio, a collaboration of news organizations across the state that sponsor “table conversations” between journalists and citizens to explore their biggest challenges. The aim is to give greater voice to Ohioans while rebuilding their trust in Ohio media. Since late 2015, the collaborative has held two dozen community conversations in nearly every part of the state, from Cleveland to Cincinnati and Lima to Marietta.

But rebuilding trust in the media is a long road that faces partisan challenges of its own, says Jeff Blevins, an associate

professor and head of the journalism department at the University of Cincinnati. “We don’t just have a journalism crisis. We have a knowledge crisis,” he says. “We don’t have a common way to assert facts as truth.”

The problem in finding common ground today “is that we have to want it. We have to value it,” he says. That may no longer be true, especially among conservatives, according to a recent experiment with local news conducted by Blevins and Brian Califano, an associate professor of political science and journalism at UC.

The experiment was an online survey of 503 Cincinnati area adults categorized by their political affiliation: Democrat or Republican. It randomly assigned 274 of the adults to a local TV news story featuring a group of residents discussing different issues and with the term “common ground” mentioned three times in the script. A second group of 260 adults was exposed to the same news story without the term “common ground.” Both versions carefully avoided any mention of political terms, politicians, or policies.

The online participants were then asked how much they trusted the reporting in the story they were shown. The inclusion of the term “common ground” made a significant positive impact, but only on the Democrats in the survey, not the Republicans, Blevins says. “If people aren’t really interested in finding common ground, what can the news media do about it?”

Baker recommends a book that is required reading for his honor students at Wittenberg, Michael Austin’s We Must Not Be Enemies: Restoring America’s Civic Tradition. The title is based on a line from Abraham Lincoln’s first inaugural speech when he pleaded with the South for unity even after seven states had already seceded.

Austin’s book calls on Americans “to realize we’re all in this big experiment we call democracy together,” Baker says. “We need to recognize that we’re all friends in the sense that we live together in the same community.” In order to move the country forward, “we have to be willing to reach out to everyone and recognize that, in a democracy, we should expect to disagree and expect to have very divergent opinions.”

Agreeing to disagree with others isn’t enough, Baker says. “In traditional rhetoric, agreeing to disagree means we have to talk. It will be hard, and there may be times when we have to walk away from it. But let’s agree to keep working on it to see where we can agree.”

Support for Ohio Civics Essential is provided by a strategic grant from the Ohio State Bar Foundation to improve civics knowledge of Ohio adults.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the Ohio State Bar Foundation.