Learning to treat nonprofits as more than charity cases

Author Dan Pallotta and local nonprofit leader Tom Callinan are trying to change public perceptions of nonprofit organizations in order to improve their effectiveness and "change the world."

The U.S. nonprofit sector has been set up to fail, Dan Pallotta says. A centuries-old Puritanical approach casts all nonprofits as charities in Americans’ eyes, making it difficult or impossible for organizations to reinvest money in themselves and thus create stronger and more effective operations.

Nonprofits are usually forced to forego the kinds of basic business tools that for-profit businesses invest in every day — from new computers and basic building repairs to employee training and marketing — to ensure that “overhead” remains low. The organizations might save themselves from the “temptation” of overspending, but at what cost?

“Why have our breast cancer charities not come close to finding a cure for breast cancer or our homeless charities not come close to ending homelessness in any major city,” author and advocate Pallotta asks in a 2013 TED Talk. “Why has poverty remain stuck at 12 percent of the U.S. population for 40 years? The things we’ve been taught to think about giving and about charity and about the nonprofit sector are actually undermining the causes we love and our profound yearning to change the world.”

Pallotta’s books Uncharitable: How Restraints on Nonprofits Undermine Their Potential and Charity Case: How the Nonprofit Community Can Stand Up For Itself and Really Change the World lay out the basic framework for his latest endeavor, the Charity Defense Council. Tom Callinan, former Cincinnati Enquirer editor, serves on its advisory board.

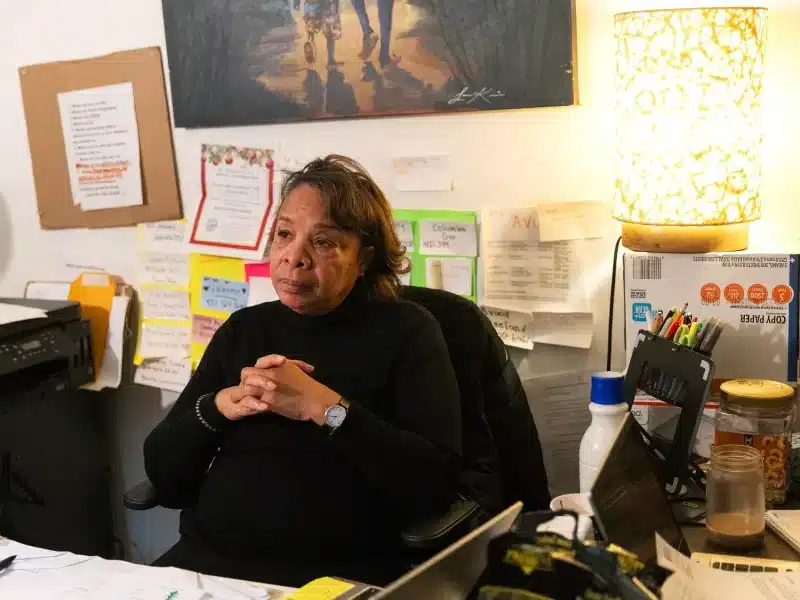

After retiring from journalism, Callinan threw himself into working with local nonprofits like Charitable Words, which he founded and still directs, and Social Venture Partners. Those efforts have connected him with dozens of other local and national nonprofits.

“I never knew how hard it would be,” Callinan says. “Especially raising money.”

Since Pallotta began aggressively agitating on behalf of the nonprofit sector, Callinan says he’s begun to see a slow shift on how nonprofits and their funders approach their work and giving.

“You hear more and more discussion about impact now, not overhead,” he says. “The whole industry is starting to get that now, and Dan has certainly been a catalyst for that.”

Pallotta points out that nonprofits often lose their effectiveness when they don’t invest in basic business tools, making it nearly impossible for them to actually accomplish the lofty goals they seek. The misguided “overhead myth” creates insurmountable obstacles to moving the needle on causes we hold most dear — poverty, homelessness, curing cancer, treating AIDS and so on.

“These social problems are massive in scale, and our organizations are tiny up against them,” Pallotta says in his TED Talk. “And we have a belief system that keeps them tiny. (But) which makes more sense: Go out and find the most innovative researcher in the world and give her $350,000 for research, or give her a fundraising department and use the $350,000 to multiply it into $194 million for her breast cancer research?”

Pallotta says the current “overhead myth” view of nonprofits stems from a concept created 400 years ago when the Puritans ventured to the New World to escape persecution and make their fortunes. They considered the very practice of making money to be sinful, requiring penance, which they turned into charitable giving. Their 5 percent tithe to charitable causes (in those days more direct contribution to poor individuals than to social service organizations) created the moralistic framework that still guides our thinking about giving to this day.

Pallotta experienced the “overhead myth” firsthand through his own nonprofit, Pallotta TeamWorks, which he founded in 1994 to raise money via multi-day biking and walking events. He raised funds to benefit AIDS and breast cancer charities, and the hugely successful events netted $305 million (after all expenses) in nine years.

Suddenly, in 2002, major sponsors began to abandon TeamWorks. There had been a lot of negative press around his organization, specifically regarding its overhead expenses — in his case, a full 40 percent of all revenue was being used to provide better customer service and create magic experiences at the events while investing heavily in marketing and fundraising.

In short order, press attacks shuttered the TeamWorks doors, 400 jobs evaporated overnight and AIDS and breast cancer charities lost some of their biggest annual fundraising events. Assuming that Pallotta’s success would have continued otherwise, those same causes have cumulatively lost hundreds of millions dollars in the years since.

Callinan recalls the first time he heard Pallotta speak while in California for a conference.

“He talked about the media and how the public does not understand these ideas (of the overhead myth),” Callinan says. “I walked up to him afterwards and said, ‘You have just changed the way I think about this issue after 35 years in the media business.’”

He says he then began to wonder, “How much damage have I done by not understanding these ideas? How many times (while at The Enquirer) did I order a little graphic showing ‘overhead’ to print alongside a story about a nonprofit?”

Callinan points out that local organizations such as People’s Liberty and ArtsWave have funding models that look more at impact than at how every dollar is spent. They recognize that training, buildings and computers are important tools and that, without them, nonprofits might be less effective.

Pallotta established the Charity Defense Council to combat our counterproductive approach to and perceptions about charitable giving. It’s currently collecting feedback on an initiative called Rethinking Charity, which asks people to watch Pallotta’s TED Talk and take a short survey to collect their impressions. Watch the talk here and take the five-minute survey via a link on the page.

Director of Mobilization Jason Lynch says that survey results so far have already helped to create a stronger framework for the Council’s mission and recruit interested individuals to the cause, and he’s hoping that the data will eventually help make the case for additional funding for the Council.